Recreating the bakery-style sausage bun

by Amanda Nell Eu08 Nov 2021

One home cook turns to dough softeners and bread improvers to create the soft, squishy texture we’ve come to love in a classic sausage bun. Photos by Amanda Nell Eu.

There is something so nostalgic to many of us when it comes to sausage buns. Maybe because there is no definitive name for them in the English language, they can sometimes be mistaken for hot dog buns or sausage rolls. But aside from what they are called, if you know you know. These iconic baked goods are frankfurters wrapped and baked in soft squishy white bread, the snack buns of childhood memories that are found in every Chinese bakery all over the world.

Here in Malaysia, you can find these buns in all local-style bakeries as well as convenience stores all over. Individually wrapped in clear plastic bags or displayed in self-service shelves, they never seem to get stale whether you keep them in the fridge or leave them out on the counter over a night or two.

The Asian palate for breads used to be soft, white and sweet, unlike the crusty harder breads that we find in the West. I remember even as a child, my mother would tell me to scoop out the soft bits of my Western dinner rolls to avoid the crust, so as to have a more pleasant eating experience.

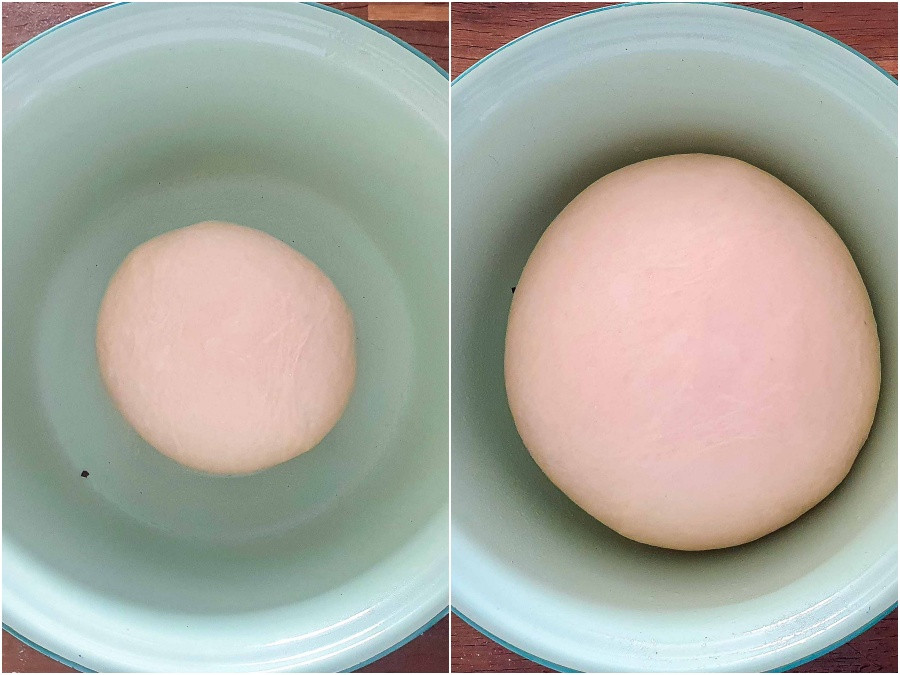

The soft, squishy texture we’ve come to love comes from the tangzhong method of baking bread which entails cooking a portion of flour and liquid prior to adding the rest of the dough ingredients. This method allows the dough to absorb more hydration, while still being easily workable, resulting in soft bread that can last for a long time. Most breads that you find in Chinese bakeries will use some form of the tangzhong method including the soft pillowy milk breads or even the classic Hong Kong pineapple buns. If you master this method, you can pretty much make most Chinese pastries.

In the world of bread-baking today, there is almost a religion when it comes to sourdough starters and an increasing trend in the usage of ‘healthier’ coarse flours as opposed to heavily industrialised white flour. This recipe, however, throws all these beliefs out the window, because why not?

As an avid fan of using the tangzhong method, I was keen to find out how these commercial breads kept so fresh, soft and springy for so long. I needed to get that chewy, slightly elastic white bread texture that we all grew up with, the kind that soaks up all your Milo like a sponge.

So I went straight for bread improver and dough softener sometimes used in Asian bread recipes but rarely in Western ones. There is a reason why many bakers are afraid to use this ingredient and I honestly don’t blame them. Trawling through the internet to find the exact ingredients for branded bread improvers was nearly impossible. Maybe there is something that they want to hide from us or maybe the manufacturers didn’t think of the need to list out ingredients for home bakers. I have not found the answer to this but if you are wary about what you eat and need to know about every E number you put in your body, I would advise you to give these ingredients a miss.

From my research, there is a differentiation between the two. Bread improvers consist mainly of enzymes, oxidizing agents and hydrocolloids—think better fermentation, increased dough strength and improved hydration capacity. Ingredients of dough softeners are however better-labeled and easier to find. With a texture and feel similar to shortening, they usually consist of vegetable fats and emulsifiers, which can improve dough stability and uniform crumb texture. Going through more scientific research on these ingredients I have personally come to the conclusion that bread improvers and dough softeners are safe to use within the correct amounts and ratios to your flour weight.

This recipe uses a bread improver and dough softener which I think makes a small but necessary chewy difference, however if you choose to omit them, you will still be able to achieve a beautifully home-baked sausage bun.

Read next

An introduction to pangkang

A rice staple for the Dayak community

The 101: How to avoid soggy meehoon

To soak or not to soak?

The 101: How to prepare keluak

Cleaning keluak for safe consumption