A lesson in pulses—passed down by a grandfather

by Sheela Kanagasabai26 Jan 2024

How this writer’s Ceylonese grandfather taught his multi-lingual grandkids valuable lessons about the complex world of legumes.

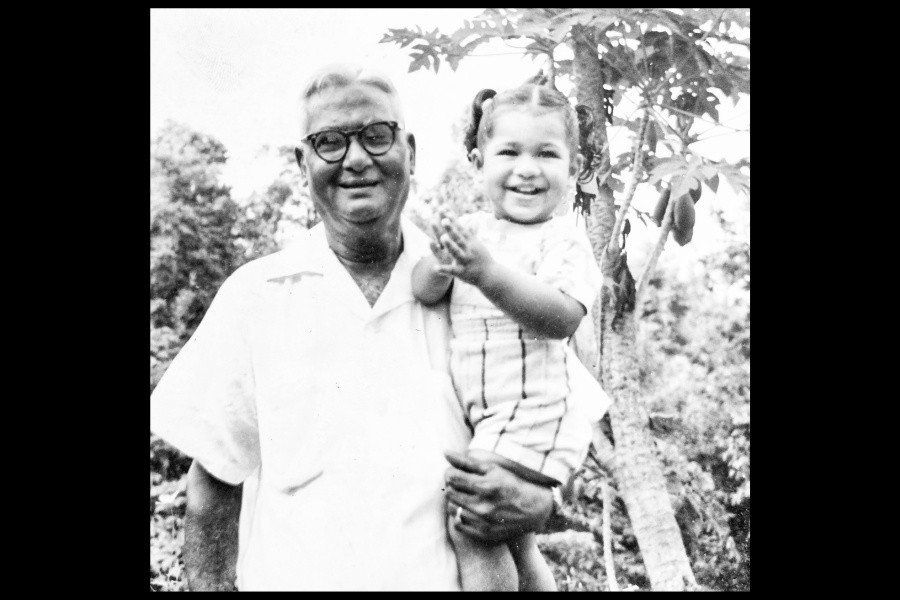

I never knew much about my paternal widowed grandfather as I only saw him over the school holidays. He, just like my father, was a man of few words, proud and obstinate in character. Since grandfather was forced to sustain himself during post-war Malaya, he learnt how to cook and turn dry legumes and blended spices into delicious things, a skill he acquired from his parents who were Sri Lankan migrants. Their usual food rations included yellow split peas, fish, rice, and oil.

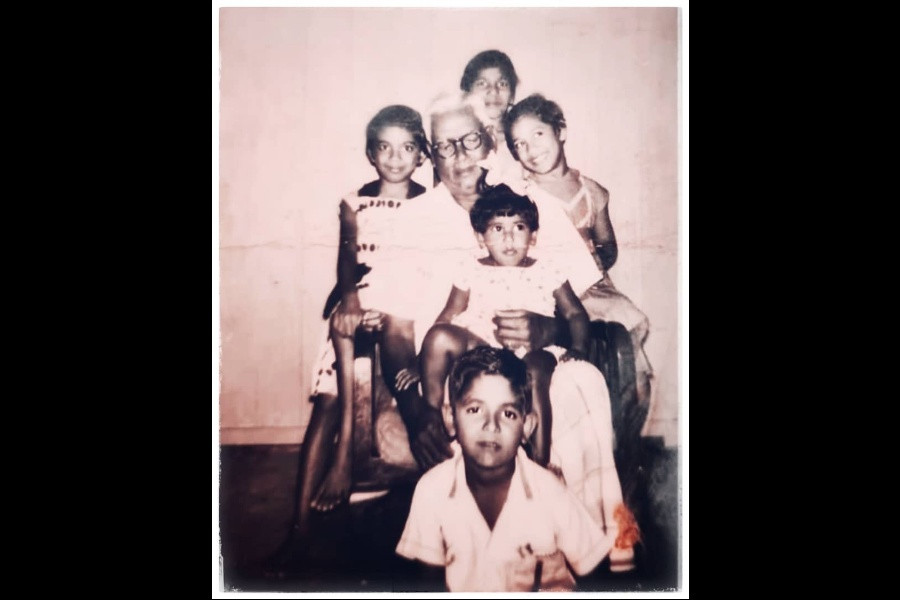

When he was in a good mood, my grandfather would be seen in his dark kampung kitchen in Seremban, stirring spicy curries over a stove powered by discarded coconut shells and charcoal. This part of the house always smelt of raw onions, garlic, chillies and a variety of fermented foods. Pulses of different colours would sit inside rusted biscuit tins; these contained protein-packed chickpeas, lentils, and dried peas. My cousins and I were truly fascinated by the different types available and eagerly watched him sieve through them with his arthritic fingers.

My grandfather took it upon himself to teach all twelve of his multi-lingual grandchildren about the various pulses that would be used in different dishes—in Tamil, Malay, and English. Pulses are part of the legume family, but the term ‘pulse’ refers only to the dried seed. They are dried legumes that grow in a pod of one to twelve seeds. These include beans, lentils, peas, and other little seeds referred to as lentils or beans. Dal is often translated to ‘lentil’ but it actually refers to a split version of a number of lentils, peas, chickpeas, or kidney beans. If a pulse is split into half, it is dal. Indian pulses are usually available in three types: the whole pulse, the split pulse with the skin on, and the split pulse with the skin removed.

One of my favourite curries my grandfather exposed me to is one cooked with broad beans and referred to in Tamil as mochai or mochakottai. They are sometimes known as field, lima, or hyacinth beans. Sold in many Indian grocery and spice shops as a dried pulse, the mochai is soaked for hours in warm water to soften its hard shell and then boiled. Other times, its outer skin is peeled off, and the beans are lightly stir-fried with mustard seeds, onions, dried chillies, and turmeric powder and served as a crunchy, salty snack. These days, a pressure cooker can be used to soften the tough exterior of the mochai in as little as 15 minutes.

Get Sheela’s grandfather’s recipe for mochai karuvadu kuzhambu here.

***

Sheela Kanagasabai is a freelance writer and self-taught baker and cook.

Read next

A father’s legacy in soy sauce

A tale of family, grief, and kicap

How my grandfather wooed his son-in-law—with peanut cake

A rare Foochow delicacy—made to impress

How my grandma’s recipes bridged a 10,000km, 20-year gap

A tale of old recipes and belonging