How my grandma’s recipes bridged a 10,000km, 20-year gap

by Emma Chong Johnston05 Apr 2021

A tale of generational love, immigration and belonging told through a hulking pile of hand-written recipe notes.

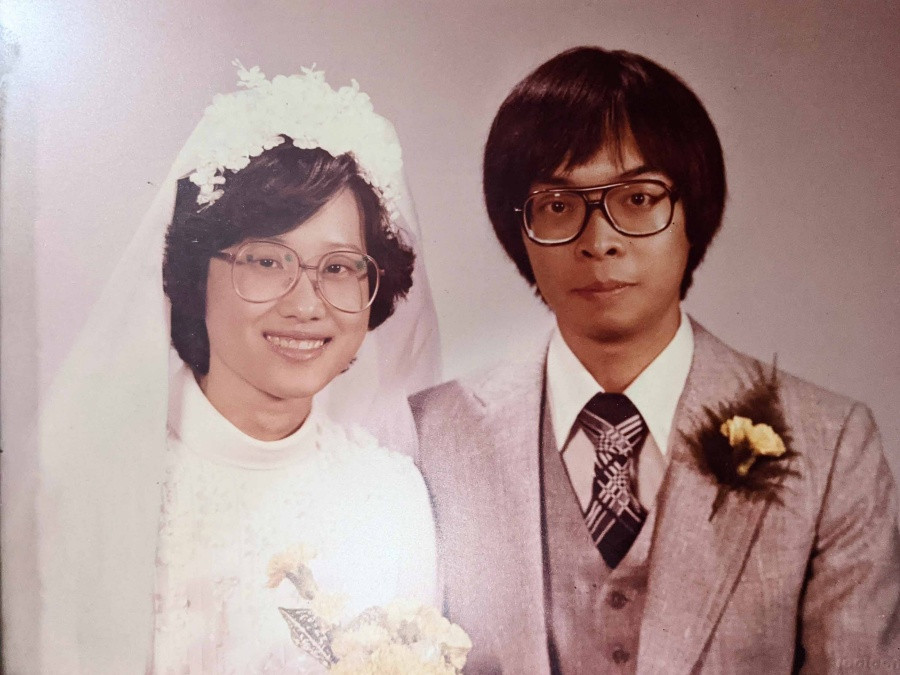

When my parents got married in 1979 and set up their marital home in England, there were several cultural forces at play. First there was, of course, the overarching theme of Britishness. My parents had both recently graduated from university in London, and before that had completed their secondary schooling at boarding school; my mother in rural Wales, my father at the seaside in Ramsgate. Upon getting married, they set up home in an inner-city London suburb. Both of my parents were keen to assimilate into their new city.

What did they bring with them from Malaysia? An appreciation for an emergency stack of Maggi Mee in the larder. An intricately carved camphor chest for storing wool jumpers in. And in my mother’s case, a folder full of type-written, photocopied recipes from her mother-in-law, supplemented by more missives regularly mailed over or slipped into the suitcases of obliging relatives and friends. These recipes were dutifully looked over and filed, and as any Asian daughter-in-law knows (especially one married to a firstborn son) (and especially one who decided with said son to set up home a 13-hour-flight away from his family), the gift of a recipe is not just a gift. It comes bearing many unspoken messages.

The context is this: My grandma is the undisputed matriarch of the family. As the eldest of eight siblings, and even more cousins, her word has always been law, her opinions fact, and her recommendations unassailable. She has always been a confident, adventurous cook, her repertoire of Nyonya and Chinese dishes supplemented with theatrical ’70s and ’80s Western dishes as she made her way from Sitiawan to Kuala Lumpur to Melaka to Cambridge and back to Kuala Lumpur. Recipes were everywhere in her house, covering the fridge door, torn from magazines, copied from friends who’d learnt them from family, jamming up the fax machine, bulking out letters sent from sisters and cousins and aunts in Canada and Australia.

But back to my mother’s file of recipes, given from one confident matriarch to one young newlywed. I found it, full of dogeared, yellowing pages interspersed with magazine tearouts (shoutout to Female magazine, a staple of the 1980s homecook), in a recent spring clean at my parents and was entranced at what a perfect time capsule it was. How a stack of recipes could tell me so much about a time, but also about my grandma’s larger-than-life personality. If you’re expecting a pristine, orderly, well-catalogued file here—gotta tell you no, that’s not what my grandma was about. Her kitchen was always messy, oil splatters on the cabinets, stacks of dirty pans left in the sink for someone else to wash up. Her cooking superpower was enthusiasm, not tidiness. Nor was she even the best cook—she would happily forget ingredients, sub in things she thought would work but definitely didn’t and regularly over or undersalt her food.

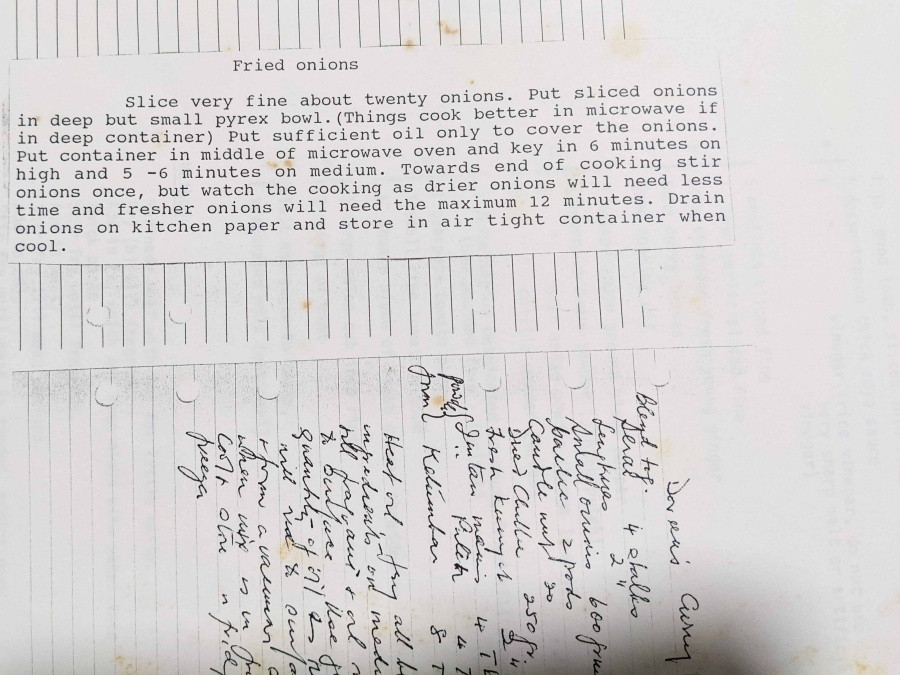

But such is the power of charisma—whatever she placed in front of us, we ate, and ate enthusiastically. It’s the charisma that shows in this random assortment of recipes. There are the classics, of course: sweet and sour pork, nasi kunyit, inche kabin, ‘The Perfect Flaky Layered Curry Puff Pastry’. There’s a typewritten paragraph about frying onions in the microwave that honestly blew my mind. A quickly scribbled half-page on ‘Doreen’s Curry Mix’. (Doreen is one of my grandaunts and one of the best cooks in the family, not that you could tell my grandma that.)

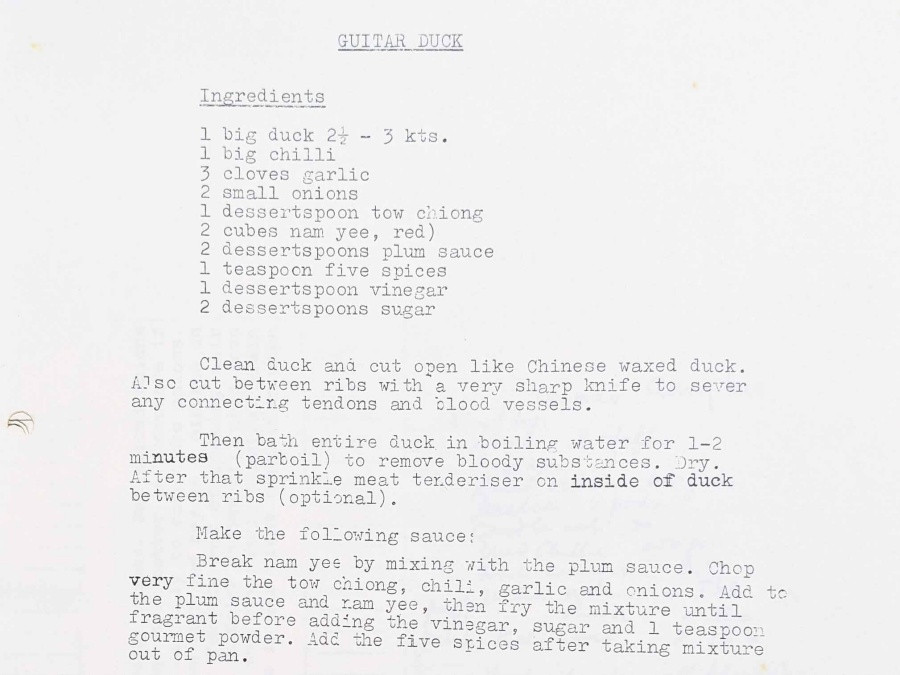

My grandma is proudly Nyonya but she didn’t necessarily prize the cuisine above any other Malaysian or regional style. Balinese chicken, Siamese curry—clearly they didn’t go in for ethnographic accuracy at the time. Then there are the showpieces, guaranteed to get the conversation going at a dinner party. Lamb Royale: deep-fried slices of lamb, drenched in Szechuan bean sauce, sprinkled with sesame seeds and served inside a ring of blanched broccoli. Guitar Duck: a spatchcocked duck (‘make sure it’s a big duck, 2 1/2–3 kts’), marinated in plum sauce, nam yue and five spice. ‘Makes an interesting roast duck,’ my grandma notes on the side. Then of course, her piece de resistance, the staple celebration piece she brought out every Christmas: a baked joint of gammon, festooned with rings of tinned pineapples and halved glace cherries, glistening with caramelised marmalade.

What did my mother, not timid, but deferent, make of this showcase of her mother-in-law’s culinary prowess and spirit of adventure? The parade of party dishes designed to impress, the litany of homecooked meals made to both nourish children but also cow them into submission. The act of cooking—showmanship for my grandma, everyday necessity for my mother—meant something entirely different to each of them. My mother’s parents were first generation immigrants from Shanghai, landing in Malaysia as teenagers with siblings to bring over from the mainland. They’d go on to run all manner of businesses here in Malaysia—dry cleaners, noodle stalls—but with four children to support in the shophouse upstairs, my maternal grandmother didn’t have the time to sit and coach my mother through family recipes. What my mother learnt she learnt by watching, glimpses stolen when she should have been doing her homework, tips waved her way by chattering aunties.

So what did she do with this hulking folio of recipes? As any good daughter-in-law would do: she cooked through them. Some of the flavours were new to her; some were just a lot punchier than she was used to. “Your grandmother used a lot of garlic,” my mother told me. “Garlic in everything.” (Interestingly, these days you could easily make the same accusation of my mother’s cooking.) The Shanghainese dishes my mother grew up with were largely subtle, steamed and fragrant. Think of the internationally loved xiaolongbao, that originated in Shanghai—delicate and brothy. None of that for my grandma. It wasn’t just garlic she was heavy-handed with; she was constantly throwing in unauthorised slugs of soy sauce, or nam yue, or just several more pinches of salt.

Nevertheless, my mother ploughed on. “I made the chicken with yam a lot, but I used pork,” my mum tells me. (A sub my grandmother would be proud of.) “I learnt how to roast lamb using her recipe; I tried making the curries but I couldn’t find all the spices in London. I used to take her recipes to the Chinese supermarkets and spend hours hunting through the aisles for all the ingredients I needed.” And even though they weren’t the dishes she grew up with, they helped my mother retain a connection to Malaysia, when post was slow and long-distance telephone calls ruinously expensive. Pork with yam is a staple in her everyday cooking now, though she didn’t remember the recipe had come from until I waved the yellowing page in front of her. She also now uses leftover roast pork in the dish, a decision which I know would both intrigue and slightly scandalise my grandma.

There was one thing I couldn’t work out when I was sifting through the pages of the file. Additions that I couldn’t imagine my grandmother cooking, or wanting to cook: traditional Yorkshire puddings; frosted grapes (coated in whipped eggwhite and sugar, if you’re interested); gravlax and sour cream tart. Seafood risotto, stuffed peppers; chestnut cake. These dishes would have left my grandma cold. Why had she put them in?

“They’re mine lah,” my mother said. “You added your own recipes to grandma’s file?” I replied, incredulously. “Of course,” she said, breezily. “She’s not the only one who can tear pages out of a magazine, you know.”

I haven’t eaten my grandma’s cooking for a while now. At the age of 93 her senses are now dulled and she spends her days drifting in and out of lucidity. As a child I lived in perpetual awe of her sharp tongue and quick wit, slugging my way through the endless thermoses of soup she would send over for my brother’s and my after-school fortification, whether we liked it or not. I’d love an afternoon bowl of lotus root and peanut soup now. I’m sure there’s a typewritten recipe for it somewhere.

To make Emma’s grandmother’s chicken with yam, see the recipe here.

***

Based in KL, Emma Chong Johnston is a writer of stories and entertainer of toddlers (but only her own).

Read next

A father’s legacy in soy sauce

A tale of family, grief, and kicap

How my grandfather wooed his son-in-law—with peanut cake

A rare Foochow delicacy—made to impress

Mastering sambal tambrinyu, the famed Kristang condiment

Sweet-tangy-salty and just right