Telling a tale of the land

by Alia Ali13 Jan 2021

Periuk speaks with Syarifah Nadhirah, author and illustrator of ‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’, about her work process and navigating the landscape of indigenous representation.

‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’ is a beautifully illustrated book on the edible plants, food, and culinary memories of the Temuan and Semai communities of Malaysia. Compiled and illustrated by artist Syarifah Nadhirah, it details many botanical elements from the Malaysian forests that nourish indigenous peoples, and passionately calls for all of us to recall the tastes of the land before they are forgotten.

We chat with the author and illustrator on her work, her process, and navigating representation in a multicultural society.

Hi Nadhirah! Please tell us about yourself and where you are.

I’m Syarifah Nadhirah and I’m in my art studio. Those are my works you see [gestures to the watercolour illustrations pinned on the wall behind her]. I come from an architecture background, and I’ve since moved on to work with anything paper-related. Stationery, corporate branding, graphic design, that sort of thing. My main interest is in botanical elements. I’ve been painting plants for as long as I can remember.

How did you arrive at the topic of ‘Forgotten Tastes’? Whose forgotten tastes are these?

One thing led to another, really! At one point it struck me to do more research on local ecology and to document endemic plants. I had a meeting with Dr Rusaslina Idrus from University Malaya, who does a lot of work with OA communities. She encouraged me to work with them as well, and brought me to a village in Labu, Negeri Sembilan. It was a humbling experience to celebrate Christmas with them, and one of the ladies brought us on a garden tour in her edible backyard.

Shortly after that, I was accepted into a residency at Rimbun Dahan. For those who haven’t been to the arts centre, it’s basically a botanical haven, rich with edible plants and trees. Then the pandemic happened. I tried to do my research online, but my work is so visual. So whenever the MCO was relaxed, I would make plans to go to OA villages.

As for ‘Forgotten Tastes’, well, it’s more of this generational knowledge that’s beginning to disappear from both the indigenous communities and almost gone within the majority communities of Malaysia. We all lived off the land at some point, and many of us still do. This is an attempt to preserve some of the knowledge for future generations.

Tell us more about the book. We’ve just received it in the mail and it looks like a wonderful mini encyclopaedia.

‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’ celebrates indigenous plants and food diversity. What can we consume other than what’s on the grocery store shelves? What have we been missing out on? We have so much to learn from them, instead of them learning from us. In the book there are mostly watercolour illustrations and descriptions of the plants I encountered. I included excerpts on the kampungs I visited and the portraits of the people I met. I also wanted to include the indigenous names of the plants instead of just scientific names, because that knowledge needs to be preserved too.

How many places did you go to? Which OA groups did you focus on?

Well, I had originally intended to go to more than one village to record the plant life, but one place already had so much for me to document. So I focused mainly on Semai and Temuan communities, because it was easier for me to get to their villages from KL, especially because of MCO travel restrictions.

Who were your points of contact during this process?

When I was still at Rimbun Dahan, I met Raman Bah Tuin, a Semai from Gombak, and I also knew Temuan artist Shaq Koyok. Shaq brought me to Pulau Kempas and the Kuala Langat forest, and introduced me to his family.

What was the most valuable thing you observed?

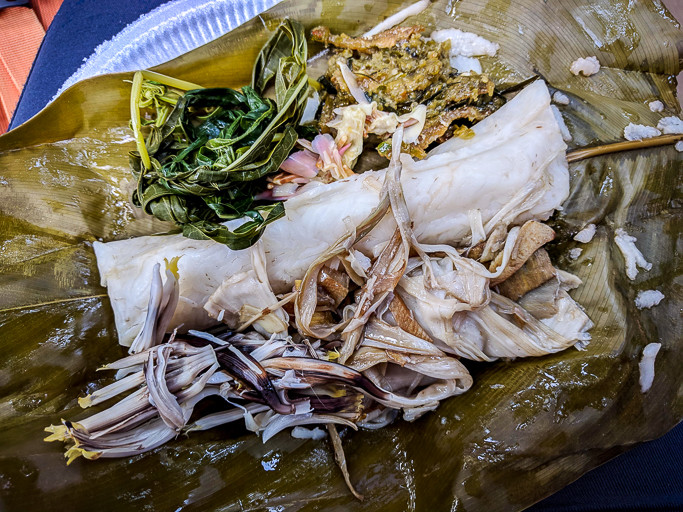

The relationship that Orang Asli have with food. They deal mostly with plants because meat is not readily available, which means that they have come up with really creative ways to cook things. For example, Kak Lisa had prepared a dish called ubi kikir or ubi sangai for a week as it had to go through some sort of fermentation, hence we only saw the process. And the second time we went, we had the opportunity to taste the outcome which had turned into granules upon frying. They treat plants and food in a holistic, no-waste way, and rely on things like bamboo and leaves as utensils and cooking vessels.

Tell us more about the challenges during the documentation process.

My guides were generous and kind, but there were more than a few plants that I was told not to draw or write about. They’re too valuable, and plant poaching happens a lot, physical exploitation. So there was a lot of communication between me and my contacts (Raman Bah Tuin, Samsul Senin, Lisa Koyok) about whether I was allowed to publish information on certain plants.

For example, Raman grows a garden on the edge of the jungle. He said it’s already quite hard to find plants, because a lot of people know about this place and just take what they can find, like tongkat ali, kacip fatimah, and pucuk manis. Even when I was in the forest with Raman, there were random people with parangs, plucking what they wanted.

So there’s less respect for sustainable regrowth now that many are harvesting for profit?

Yes, definitely. And every forest that I visited was going through its own challenges. The Semai village in Gombak was already built in the 1970s. It grew organically to what it is now, and at some point there was a highway built behind the village. Drivers on the highway would throw trash out their windows, and it would often land in Sungai Gombak and the village below. Weekly cleanups of the river need to be done.

Wow. Not caring about the forest or animals is one thing, but it’s clear from what you’re saying that many don’t realise there are actual humans who live in or rely on the forest.

Exactly. In the case of the Kuala Langat Forest Reserve, it’s an ancient forest, a primary forest that has never been deforested or replanted. When the pandemic happened and people started losing their jobs, they couldn’t shop at the markets like they used to. So they returned to the forest as a source of food, especially since it is difficult to transport food supplies into the villages.

What are your thoughts as a Malay person working with Orang Asli knowledge? How do you reconcile that majority/minority mindset, in light of all the race struggles still happening worldwide in 2020 that are on the news?

I grew up Malay, and I find it very problematic to see how detached the majority races are from the indigenous people, and how little is known of the Orang Asli culture. I hope that with this book, people can read about the plants through the lens of those who shared it with me.

I have to be respectful at every step that I take, especially with regard to consent and educating myself about their community and struggles, and keeping true to everyone’s intentions. I am not a saviour in any way. My intention is to draw these plants, to compile them, and get their perspectives on it. I presented this book to them so they can see how it’s a way for them to preserve their knowledge.

Some people may view your name on the cover of ‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’ as you ‘taking credit’ for this knowledge, instead of it simply meaning that you are the author (which you are!). And in these fraught times of representation politics, that concern is extremely valid. How will you respond to that?

It’s mainly because of authorship. Yes, I gathered the knowledge from different communities, but it’s also a question of who produced the artworks and whose experiences are portrayed. It’s also an issue of practicality in terms of book publishing, to be honest! I originally did not want my name on the cover, but I spoke to friends in Indonesia who have done work with their indigenous communities as well. They suggested that I use a Creative Commons license, which encompasses how the work was gathered with the community, and how it will be shared for educational purposes.

What are your future plans now that ‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’ is out in the world?

I plan to do even more research. One of my next projects is called ‘Mapping Indigeneity: With Plants’, which is not meant to be a database, but an introduction to indigenous plants. I am working on publishing a selected handful of edible plant illustrations on a microsite, in relation to the book. There are also potential collaborations with fellow friends who work with the OA communities, to document their food and recipes.

How do we find out more about Orang Asli cuisine?

Just talk to someone! Or get in touch with OA communities nearby. They would be more than happy to talk about their indigenous food to those who are interested. There’s a lot of material about indigenous plants in this country, but not about indigenous cuisines.

Love that advice, especially since our cultural histories are so oral. And it wasn’t until the last century that people here began to earnestly document culture on paper.

I think it is important for such knowledge to be shared, in order for people to understand the urgency to protect our already endangered forests.

To learn more about ‘Recalling Forgotten Tastes’, click here.

Read next

Is our food Malaysian enough?

Rethinking our 'national' cuisine

How are frontliners breaking fast?

Essential workers on buka puasa plans

Keeping Kadazandusun cuisine alive for another generation

Kadazandusun cuisine and its future