The collective prejudice against beef-eating Dalits in Malaysia

by Miriyam Ilavenil21 Oct 2024

Caste-Hindus in Malaysia often denigrate beef-eating, as cows are perceived as sacred in Hinduism. However, this has led to the marginalisation of beef-eating Paraiyars—a group indigenous to Tamil Nadu—in West Malaysia.

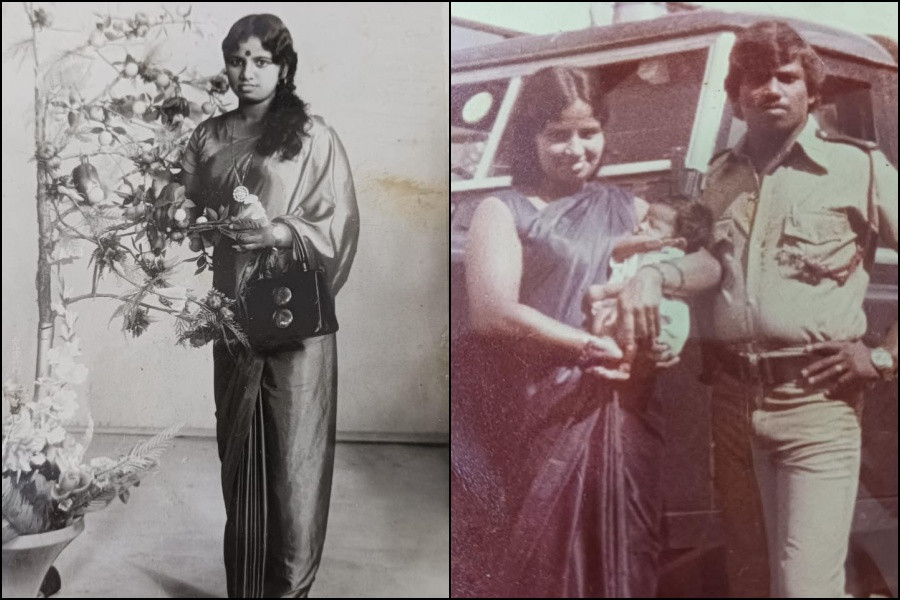

In 1925, 17-year-old Thangamaal, a native of Chengalpattu in Tamil Nadu, boarded for colonial Malaya with her husband when she was still three months pregnant with her eldest child. She arrived at Teluk Intan’s Batang Padang Rubber Estate, where she worked as a rubber tapper. She built her life there and later gave birth to her youngest child, Muthuvelo Tangakrishnan Neelavanan, in 1952.

Thangamaal was a Paraiyar, an indigenous Tamil tribe that was forced to become ‘untouchable’ by Hindu society.

Scholar P. Velusamy’s research shows that in the mediaeval period, Tamil vendars (landowners) adopted the caste system of Brahmin migrants in order to protect and nurture their power over lands and people. This led to the subjugation of many tribes, like the Paraiyars, into becoming landless enslaved people who were owned by caste-Hindu feudals.

The caste system sees Brahmins—who practice vegetarianism—at the top of the hierarchy, followed by Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and the Shudras. The Dalits, a popularised term for all ‘untouchable’ castes, exist outside this system and are the most brutalised by it.

From the 1830s, caste-feudalism was used as a social structure by British imperialists to forcefully displace hundreds and thousands of Dalit and lower Shudra Tamil peasantry, like Thangamaal, to work on plantations in British colonies through the system of indenture labour.

Scholar Benedicte Hjejle noted that because the colonial administration failed to record the castes of migrating Tamil workers, there is currently no estimate of how many people from each specific caste have been brought to the colonies—including British Malaya at the time.

However, scholar Rajshekar Basu wrote that within the Malayan context, a majority of Tamil workers had been Dalits from the Paraiyar and Pallar castes. Documents showed that the colonial administration, which practised caste bigotry, found Tamil-Dalit workers to be the most ideal for plantation labour because they were deemed to be ‘docile’ and ‘obedient’.

‘Yes, I eat beef, so what?’

In the estate, Thangamaal, despite not knowing how to read or write, raised her son, Neelavanan, with stories from the Mahabaratham, Ramayanam, as well as Tamil Bhakti songs. In spite of her devotion towards Hinduism, she was a woman who liked eating beef, a meat often seen as ‘impure’ by caste-Hindus.

“Once, my mother bought beef from the town, and when the neighbours asked her what she was cooking, she said mutton. When I asked my akka (sister) why amma (mother) said that, she told me that people [Hindus] who pray can’t eat beef,” recalled Neelavanan.

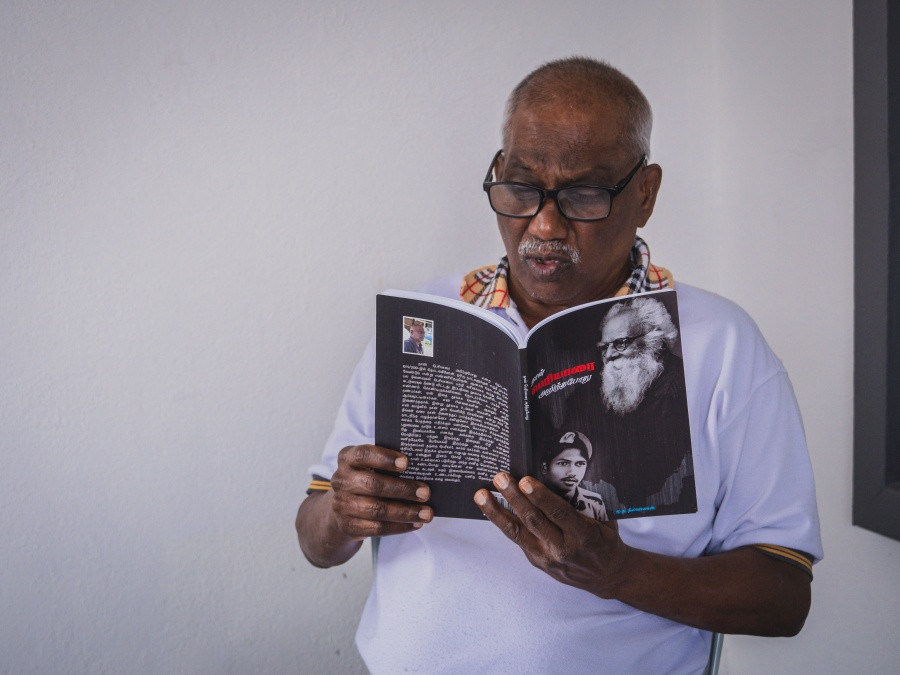

As Neelavanan grew up, he understood that Hindu religiosity surrounding beef was a weapon against Dalits who consume it. “People around me eat mutton, chicken, water monitors, pork—they eat everything,” he said. “But when it comes to beef, they say that it is god. They brand [Hindus] who eat beef as coming from a certain caste. We are buying [beef] with our own money; we did not steal or beg for it. Yes, I eat beef, so what?”

Over time, however, the culture of eating beef has deliberately declined among Dalits in Malaysia as a way to escape casteism and adapt to caste-Hindu practices. This shift can be seen in Neelavanan’s own family, where his siblings and relatives refuse to eat beef and even scrutinise him for his beef-eating habits.

The politicisation of vegetarianism

Karan Karki, a Tamil Nadu-based Dalit writer, has historicised the deification of cows and vegetarianism, attributing it to Brahminism’s attempt to achieve hegemonic control of Tamil society.

He said that in the 7th century, many Jains and Buddhists were documented to be brutally slaughtered by proponents of the caste system. This religious persecution is said to have led to Hinduism appropriating Jain and Buddhist traditions of vegetarianism. As an attempt to gain social mobility in this setting, the feudal Tamils at the time began mirroring the vegetarian lifestyle of the Brahmins, a practice that still exists today.

“Paraiyars, the indigenous Tamils, did not adapt themselves to this and maintained their practice of eating beef,” said Karan. “And because the Dalit people were consuming beef, the particular meat became associated with impurity and untouchability. Today, beef is associated with Muslims by caste-Hindus in order to further alienate them.”

There has been documentation of Tamils consuming beef in Sangam literature—estimated to have been written between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE—as well as beef being consumed and sacrificed in Hindu scriptures like the Manu Dharmam, the Manusmriti, and the Mahabharata.

“Even Hindu religious leaders such as Sankaracharya and Vivekanada praised the consumption of cow meat as a devotional practice of Hindus,” added Karan.

Malaysian-Tamil writer Navin Manogaran said that the marginalised reality of Malaysian-Tamils may have influenced the cultural shift towards vegetarianism.

“Tamils [in Malaysia] are insecure because they do not possess political agency, they are seen as outsiders who were brought here,” said Navin. “Thus, they choose to adapt to [Brahminical beliefs] as an attempt at social elevation.”

As a native of Lunas, Kedah, Navin recalled that in the ’70s, his hometown and neighbouring village were steeped in caste politics, particularly apparent through local temple management controlled by a caste-Hindu community that adapted Brahminism.

“When the Muniyandi temple was handled by a poosari (non-Brahmin), meat was allowed; however, when it became a Muneswaran temple, and the aiyer (Brahmin) took over, meat was seen as impure and vegetarianism was seen as holy,” said Navin.

In the narrative of present day Malaysian society dominated by Tamil caste-Hindu hegemony, an Indian is a Hindu, and a Hindu never consumes beef. There is little room for complexity when cultures are forced to be amalgamated for mass consumption. Indian restaurants in Malaysia advertise all sorts of meat cuisines except for beef, while the only Indian restaurants that do serve beef are Tamil-Muslim mamak shops that are often perceived as being outside or against ‘Indian heritage’.

Beef as a symbol of animosity

The estate Neelavanan grew up in was predominantly filled with Hindu Paraiyars, as well as seven Telugu-Hindu families, and three caste-Hindu Tamil families.

“We had a family bond, addressing each other with terms like maama and akka, but still, some [caste-Hindus] would not come to our house to eat,” recalled Neelavanan.

This habit would bother him further when caste-Hindus in his estate would have no qualms about eating at a Chinese house nearby, where wild dogs hunted from the estate would be consumed.

“Once, when I was a very young boy, I went to the town, and a Malay lady said ‘poda paraiya’ (shoo, pariah) to me, and I wondered why she was speaking this way to me,” said Neelavanan. “Another time, when I worked in a petrol bunker, I asked a Chinese customer if he wanted the expensive oil or the normal oil, and he replied, ‘taruk itu paraiya punya minyak’ (put that pariah oil). That’s when I realised that the practice of other people degrading Dalits [was spreading beyond] Tamil society.”

Neelavanan would go on to marry Rajaletchumy in an intercaste marriage, and unlike him, his wife had been raised in a family that didn’t consume beef. Whenever Neelavanan would buy beef from the supermarket, Rajaletchumy would cook it for him while never actually eating it herself.

After the passing of Rajaletchumy, Neelamalar, their eldest child, took over the duty of cooking for her family. “I learnt every recipe from my mother, but she never taught me how to cook beef. I just applied the same technique we use to cook mutton to cook beef,” shared Neelamalar.

So far, she has tried making malli (coriander seed) beef, beef kurma, beef pizza, beef perattal, and beef rendang, and is excited about attempting beef curry.

When Neelamalar prepares Tamil-style beef peratal, she includes spices such as fennel, cumin, coriander, pepper, cinnamon, cardamom, and clove, all of which are also used by Tamil caste-Hindus in their preparations for chicken or mutton peratal. The only noticeable difference is the flavour the meat adds to the dish.

Since her father was a Periyarist atheist, Neelamalar was raised without religion, and the only festival she grew up celebrating was the secular Tamil harvest festival of Ponggal because of her family’s strong ties to their Tamil identity. Where most Malaysian-Tamil Hindus venerate Deepavali as a core expression of their ethnic identity, many anti-caste secular Tamils instead see Ponggal as a celebration of the liberating, anti-Brahminical roots of Tamil culture.

During Pongal, Neelamalar’s mother would cook mutton as the main dish, as they preferred the rich taste of the meat, as well as beef on the side. Yet, whenever they had guests over, whether family or neighbours, they would never prepare beef for them.

“It has just always been that way,” Neelamalar said.

Get Neelamalar’s recipe for beef peratal.

***

Miriyam Ilavenil is a journalist and a descendant of displaced Tamil Dalit indentured labourers who is interested in understanding the politics and histories of South and Southeast Asia.

Read next

Beef peratal

A celebratory curry

A guide to Deepavali snacks

Titbits for the festive season

How did tinned sardines become a staple in Malaysian kitchens?

A history of canned fish in Malaysia