Does ammonium bicarbonate make a better char siu bao?

by Amanda Nell Eu22 Jan 2021

One avid home baker steams a batch of bao to test the results of this strong-smelling traditional leavening agent.

As a home baker, I’ve always found leavening agents a mystery. Truly believing in the hard and fast rule that baking is an exact science, I’ve never questioned the why or how. Things will all just work out if I put all my faith into a recipe and follow it to the exact milligram. Come 2020, when many of us turned our hobbies up to eleven, I found myself gaining more and more confidence in baking, eventually becoming interested in Chinese breads and pastries.

Trawling the internet for char siu bao recipes, I noticed an ingredient that kept popping up: ammonium bicarbonate, or chou fen (臭粉), which translates directly to stinky powder. Some recipes were adamant that the ingredient be included while some thought it was necessary. I wanted to find out for myself, so I got my hands on some in pursuit of the perfect char siu bao.

Ammonium bicarbonate is an ingredient found in many old European recipes for cookies and biscuits. It was used as a leavening agent before baking powder, and somewhere along the way, it ended up in the doughs of many traditional Chinese recipes. If you want your bao to break open and reveal its soft fluffy texture, or if you want your bo lo bao to have that signature crack on its surface, or if you wish for your you tiao to have a crispy texture upon deep-frying, you’re going to need to get acquainted with ammonium bicarbonate.

Like baking soda on steroids, ammonium bicarbonate releases both ammonia and carbon dioxide when decomposed, making it a super leavening agent. However, in the presence of high-moisture doughs such as cake batter or bread dough, the ammonia gas dissolves in the water resulting in a sharp, pungent odour in your baked product. The ingredient is therefore advised to be used in recipes for thin and crispy biscuits, rather than cakes or bread. But I was curious about its effect on buns, which had become a lockdown obsession of mine.

Upon opening the bag of ammonium bicarbonate, I could tell that the substance definitely lived up to its name. A deep inhale of the stuff reminded me of my cat’s litter box. The smell alone made me nervous about putting it into my bread dough, but who are we to question traditional recipes?

So how did it turn out?

I made two batches of char siu bao, one with ammonium bicarbonate (let’s call this Batch A), and the other with exactly the same ingredients, minus ammonium bicarbonate (Batch B). Batch A had approximately 0.6% ammonium bicarbonate in its dough (this recipe really called for a microscale), while Batch B had none.

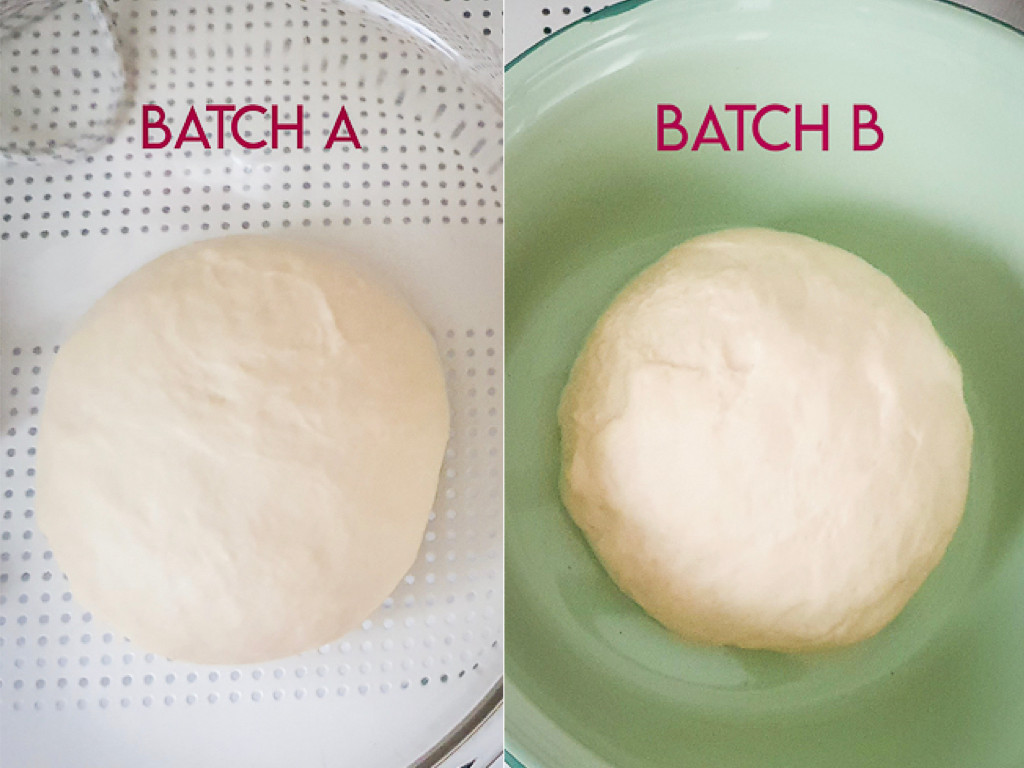

I used cake flour given that char siu bao requires a low-protein flour, and kneaded and proofed both batches of dough. Both doughs look pretty much the same here – what you can’t tell from the photo is that Batch A smelled faintly like cat urine.

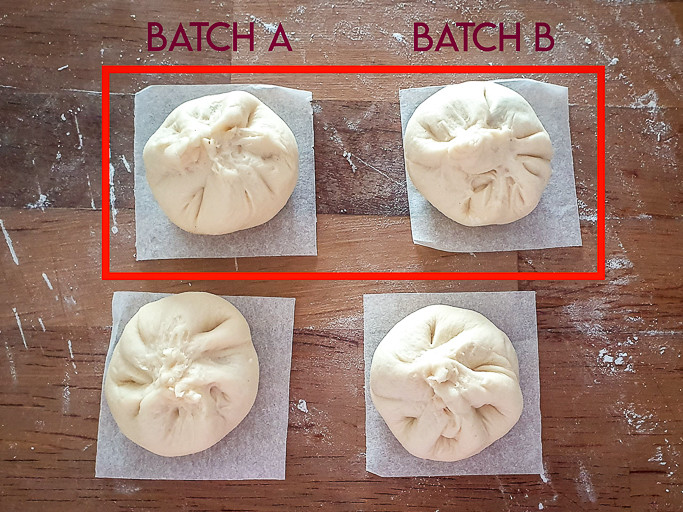

As I worked quickly to fold, fill and transform the dough into baos, I found there was once again no difference in the texture of both doughs. Both were incredibly springy and I had to work fast in the warm humid weather if I wanted to make 20 equal baos.

In the image above, I circled the two baos from each batch that would first go into the steamer. Both were stuffed with equal portions of filling and sealed, and there were no visible cracks in the dough pre-steam.

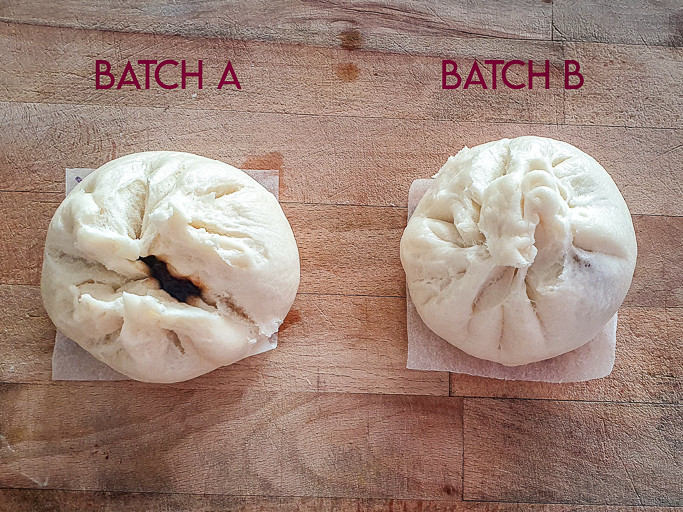

I steamed both baos for 10 minutes and these were the results.

The difference was ever so slight. Here Batch A had obviously burst open while Batch B remained intact with no dough cracks. Any shape or pattern in Batch B was simply the dough folds loosening and opening up in the steamer.

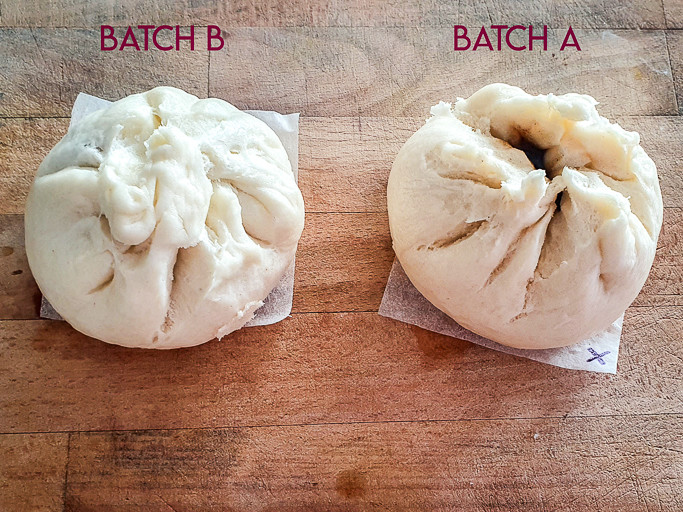

When split open, the photos below show little difference between them. If you look closely at Batch A, the bao’s outer skin layer had burst open at various places, an intended appearance of the traditional bun.

While steaming, I noticed a faint whiff of ammonia in the air, and I hoped that it was all the ammonia gas leaving the dough from Batch A. My biggest fear was that the baos would retain the smell even after they were fully cooked.

Success! Batch A didn’t emit any ammonia smell upon cooking. If I really wanted to detect the ammonia, I had to stick my nose into the bun for a big whiff – and that’s only if I knew to look out for it. In terms of texture, I would say that Batch A was slightly fluffier and puffier.

My honest conclusion is that contrary to what the purists say, it isn’t really necessary to use ammonium bicarbonate to make char siu baos at home. The leavening action compared to baking powder is rather slight and only noticeable to a bao perfectionist. With a better folding technique, I would definitely include it since I prefer the fluffier and fuller texture and the final bursting appearance of the baos. Plus, I have a whole bag of the stuff I need to use up anyway.

**

Amanda Nell Eu is a Kuala Lumpur-based cat lady and filmmaker who loves eating and cooking.

Read next

The 101: Fermentation with pangi seeds

A guide to preserving with pangi

Vegan substitutes for a Malay kitchen

Malay food without meat? Yes, please!

The painstaking process of making Foochow red wine

A quest to make wine from scratch